TAVI with the SAPIEN 3 platform: outperforming for women

The RHEIA trial is the first women-only randomised controlled trial in severe symptomatic AS in Europe and has been presented at ESC Congress, 30 August - 2 September 2024, London UK.20 This trial is designed to evaluate the benefits of TAVI for women:

Benefits

4 days

Median LoS with TAVI

(vs 9 with sAVR)

90.2%

of female patients discharged home or

(vs 49.8% with sAVR)

+20.7

KCCQ-OS improvement at 1 year

(vs 18.2 with sAVR)

TAVI with SAPIEN 3 platform was demonstrated to be superior to Surgery in women for the primary endpoint of mortality, stroke or rehospitalisation at 1 year. It reduces index hospitalisation as well and improves your patient quality of life.

TAVI demonstrated to be a safe and effective treatment option for AS female patients21,22

Womens’ unique profile: The unspoken signs of AS

Aortic stenosis (AS) affects millions of people worldwide, but did you know that women are more likely to be misdiagnosed or underdiagnosed compared with men, despite similar disease severity? The reasons are complex, but the consequences are clear: delayed treatment, poorer outcomes after surgical aortic valve replacement (SAVR) and a significant disparity in care. It’s time to shine a light on this critical issue and work towards equal access to care for all individuals affected by AS.

Prevalence

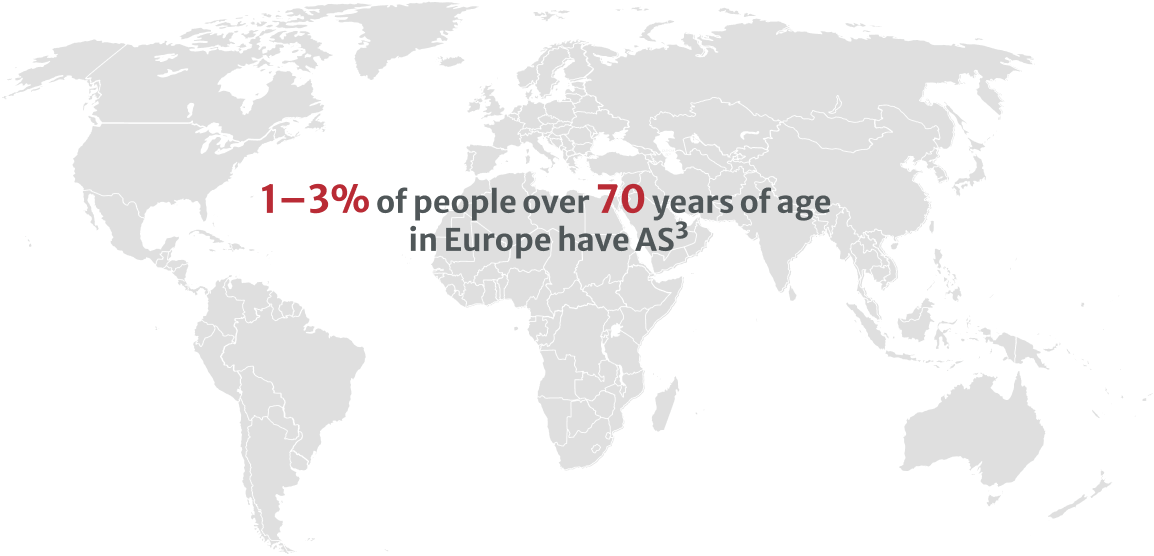

AS is a prevalent heart valve condition that progressively worsens over time, significantly affecting physical function, quality of life and overall lifespan if left untreated.1,2

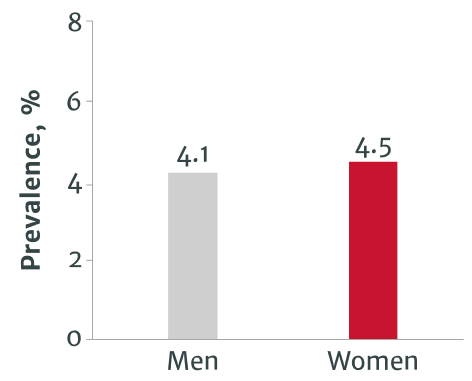

AS prevalence among men and women

According to a recent study, AS affects men and women over the age of 70 almost equally.4 However, elderly women suffer disproportionately, with higher mortality rates, after diagnosis of severe AS.2,5,6

AS prevalence in men and women4

The growing burden of AS

AS accounts for over 40% of patients with native valvular disease requiring immediate interventions, such as SAVR or transcatheter aortic valve implantation (TAVI).2,6 As the global population ages, this is expected to increase further.1

Stay ahead of the curve

Get access to exclusive resources, expert insights and updates on the latest developments in AS diagnosis and treatment. Register now and join the community working towards equal access to care for all.

Detection and diagnosis

Even though women experience the same level of disease severity as men, they are consistently underdiagnosed, leading to severe consequences and poorer outcomes. This disparity is not only unjust, but it also has significant implications for women’s health and well-being.

Delayed AS detection: Women identified at a

A striking disparity exists in the diagnosis of AS, with women being systematically underdiagnosed and identified at a later stage of the disease compared to men, despite similar disease severity.5,7

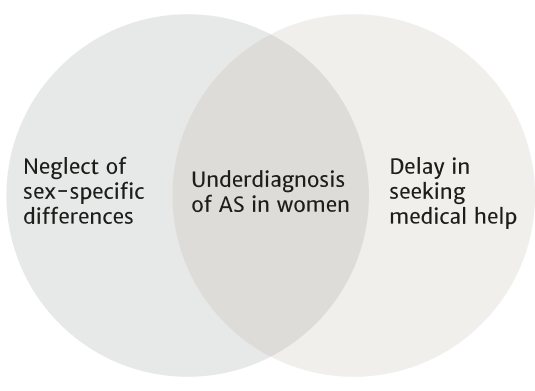

Understanding the causes: Neglect and delay in women’s

The root of this underdiagnosis can be attributed to two key issues: the widespread neglect of sex-specific differences in the presentation and progression of AS, and the tendency for women to delay seeking medical help.5,8-12 This combination results in poor clinical profiles at presentation and worse outcomes after SAVR compared to men.6,10

The consequences of delayed detection: Women’s specific profile

Women with AS are often older, frailer, more overweight and more likely to have non-atherosclerotic comorbidities, such as pulmonary hypertension, haematological disorder and renal impairment, by the time they seek treatment.5,10,13

| Parameters | Men10 | Women10 |

|---|---|---|

| Average age, years** | 76.4 | 79.5 |

| Severe frailty, % | 4.3 | 6.0 |

| EuroSCORE I, % | 14.7 | 16.5 |

| EuroSCORE II, %* | 3.6 | 4.5 |

| Haematological disorder, %* | 4.5 | 6.8 |

| Renal impairment, %* | 23.3 | 31.7 |

*p>0.05

EuroSCORE: European System for Cardiac Operative Risk Evaluation

Understanding the gender-specific differences in the pathophysiology and diagnosis of AS is crucial for improving patient outcomes. The presentation and progression of AS can vary significantly between men and women, necessitating tailored diagnostic and treatment approaches.

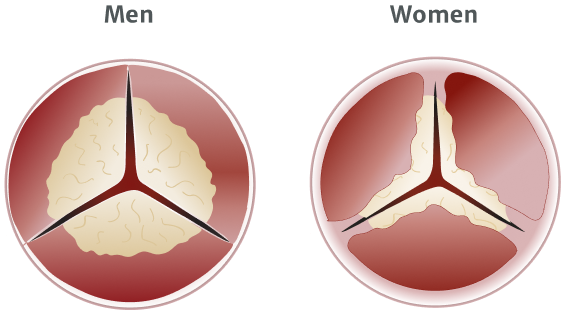

Gender-specific pathophysiology of AS: Challenges in diagnosis

The pathophysiology of AS also differs between women and men, with women exhibiting more valvular fibrosis and less calcification, making diagnosis more challenging.14,15 Women also tend to have smaller aortic valve annuli and left ventricular dimensions, complicating the assessment of AS severity using standard echocardiographic parameters.16

Referral

Despite the need for prompt medical attention, women with AS face significant disparities in referral patterns, leading to delayed treatment and poorer outcomes after SAVR compared to their male counterparts.

Disparities in referral patterns: A barrier to timely treatment for women with AS

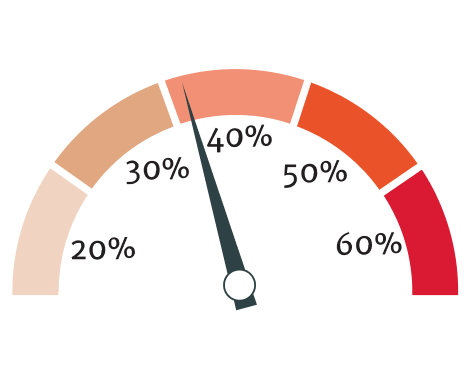

Women are 13% less likely to be referred7 and 20% less likely to receive timely treatment compared to men, which in turn leads to less favorable preoperative baseline characteristics.7,17,18 This disparity is thought to stem from surgical risk, burden of comorbidities, patient preference and other factors.17

Women are 20% less likely to receive treatment for aortic valve disease than men.18

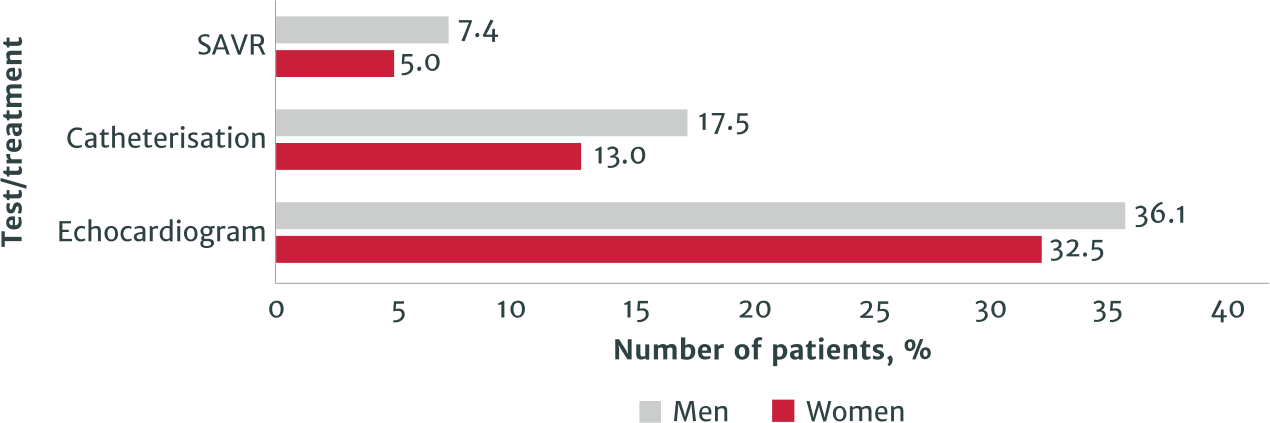

The cycle of delay: How referral patterns impact treatment

Women with AS are often diagnosed later than men because of fewer specialist referrals and diagnostic tests, leading to delayed treatment, with a lower proportion of women receiving SAVR compared with men.19

Diagnostic tests and treatment19

SAVR: surgical aortic valve replacement

References:

1 Coffey S, Roberts-Thomson R, Brown A et al. Global epidemiology of valvular heart disease. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2021;18: 853–864.

2 Caponcello MG, Banderas LM, Ferrero C et al. Gender differences in aortic valve replacement: Is surgical aortic valve replacement riskier and transcatheter aortic valve replacement safer in women than in men? J Thorac Dis. 2020; 12: 3737–3746.

3 Zakkar M, Bryan AJ, Angelini GD. Aortic stenosis: Diagnosis and management. BMJ. 2016; 355: i5425.

4 Danielsen R, Aspelund T, Harris TB et al. The prevalence of aortic stenosis in the elderly in Iceland and predictions for the coming decades: The AGES-Reykjavík study. Int J Cardiol. 2014; 176: 916–22.

5 Tribouilloy C, Bohbot Y, Rusinaru D et al. Excess mortality and undertreatment of women with severe aortic stenosis. J Am Heart Assoc. 2021; 10: e018816.

6 Panoulas VF, Francis DP, Ruparelia N et al. Female-specific survival advantage from transcatheter aortic valve implantation over surgical aortic valve replacement: Meta-analysis of the gender subgroups of randomised controlled trials including 3758 patients. Int J Cardiol. 2018; 250: 66–72.

7 Bienjonetti-Boudreau D, Chouinard I, Clavel M et al. Impact of sex on the management and outcome of aortic stenosis patients. Can J Cardiol. 2019; 35: S54-S55.

8 Fuchs C, Mascherbauer J, Rosenhek R et al. Gender differences in clinical presentation and surgical outcome of aortic stenosis. Heart. 2010; 96: 539–45.

9 Nkomo VT, Gardin JM, Skelton TN et al. Burden of valvular heart diseases: a population-based study. Lancet. 2006; 368: 1005–11.

10 Steeds RP, Messika-Zeitoun D, Thambyrajah J et al. IMPULSE: The impact of gender on the presentation and management of aortic stenosis across Europe. Open Heart. 2021; 8: e001443.

11 Gaede L, Di Bartolomeo R, van der Kley F et al. Aortic valve stenosis: What do people know? A heart valve disease awareness survey of over 8,800 people aged 60 or over. EuroIntervention. 2016; 12: 883–9.

12 Gaede L, Sitges M, Neil J et al. European heart health survey 2019. Clin Cardiol. 2020; 43: 1539–1546. Erratum in: Clin Cardiol. 2021; 44: 731.

13 Goliasch G, Lang IM. Impact of sex on the management and outcome of aortic stenosis patients: A female aortic valve stenosis paradox, and a call for personalized treatments? Eur Heart J. 2021; 42: 2692–2694.

14 Summerhill VI, Moschetta D, Orekhov AN et al. Sex-specific features of calcific aortic valve disease. Int J Mol Sci. 2020; 21: 5620.

15 Peeters FECM, Doris MK, Cartlidge TRG et al. Sex differences in valve-calcification activity and calcification progression in aortic stenosis. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2020; 13: 2045–2046.

16 Masiero G, Paradies V, Franzone A et al. Sex-Specific Considerations in Degenerative Aortic Stenosis for Female-Tailored Transfemoral Aortic Valve Implantation Management. J Am Heart Assoc. 2022; 11: e025944

17 Lowenstern A, Sheridan P, Wang TY et al. Sex disparities in patients with symptomatic severe aortic stenosis. Am Heart J. 2021; 237: 116–26.

18 Stehli J, Zaman S, Stähli BE. Sex discrepancies in pathophysiology, presentation, treatment, and outcomes of severe aortic stenosis. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2023; 10: 1256970.

19 Palacios-Fernandez S, Salcedo M, Belinchon-Romero I et al. Epidemiological and clinical features in very old men and women (≥80 Years) hospitalized with aortic stenosis in Spain, 2016–2019: Results from the Spanish hospital discharge database. J Clin Med. 2022; 11: 5588.

20 Eltchaninoff H, Bonaros N, Prendergast B et al. Rationale and design of a prospective, randomized, controlled, multicenter study to evaluate the safety and efficacy of transcatheter heart valve replacement in female patients with severe symptomatic aortic stenosis requiring aortic valve intervention

(Randomized researcH in womEn all comers wIth Aortic stenosis [RHEIA] trial). Am Heart J. 2020; 228: 27–35.

21 Mack MJ, Leon MB, Thourani VH et al. Transcatheter aortic valve replacement with a balloon-expandable valve in low-risk patients. N Engl J Med. 2019; 380: 1695–705.

22 Popma JJ, Deeb GM, Yakubov SJ et al. Transcatheter aortic-valve replacement with a self-expanding valve in low-risk patients. N Engl J Med. 2019; 380: 1706–715.

Medical device for professional use. For a listing of indications, contraindications, precautions, warnings, and potential adverse events, please refer to the Instructions for Use (consult eifu.edwards.com where applicable).

PP--EU-8668 v2.0